Trying to understand the relationship between creativity and intelligence has always been intriguing to me. As a young person, I assumed there was a direct relationship and my later interest may be a product of wanting to know how wrong I was.

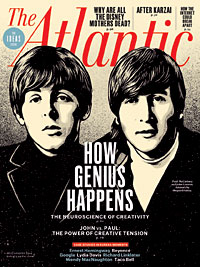

The rabbit hole I went down in pursuit of an answer to the question was an article which appeared last year in The Atlantic. [1] It’s written by American neuroscientist Nancy Andreasen, who has spent decades studying creativity and genius, whether it is dependent on high IQ—and why it is so often accompanied by mental illness.

At the outset, I will say that our varying definitions of creativity, intelligence and insanity (or more gently, mental illness) are part of the problem in drawing relationships between the concepts. Interestingly, Andreasen associates genius with creativity as opposed to intelligence. For the purposes of this discussion, let’s go with her definitions:

Creativity: the ability to produce something that is novel or original and useful or adaptive.

Intelligence: what the standard (Stanford-Binet-based) IQ test measures.

The Creative Process: recognising relationships, making associations and connections, and seeing things in an original way and/or seeing things that others cannot see.

Andreasen started with neuroimaging studies using a technology called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), where you attempt to capture brain activity in specific areas of the brain during brief moments while subjects are performing a specific task.

The first trouble is identifying the function of specific areas within the brain’s massive cerebral cortex called the association cortices. These association cortices interpret and make use of the specialized information collected by the primary cortices handling visual, auditory, other sensory input and motor control. The next problem, of course, is determining what your subjects can be doing or thinking while lying in a clanking, claustrophobia-inducing sewer-pipe (imaging machine) that’s a reliable surrogate for creative thinking.

The most interesting finding from this brain imaging research:

Creative people (defined as high creativity recognised by their peers in a literary-focussed university context) have higher activity in the association cortices than a ‘normally creative’ control group during restful mental ‘free association’ exercises. The pattern was true for both artists and scientists. So there appears to be a physiological basis for what we think creativity is (the definition above), and support for the idea that much great creative thought comes from a state of mental relaxation—or at least some separation or break from the task at hand.

We need to qualify this though: free association thinking does not lead to the creative person’s eureka moment on its own. There needs to be a long process of understanding the issue/problem at hand, and in most cases, study of the thinking by others that has come before. Newton’s discovery of the laws of gravity did not result from an apple falling on his head—his eureka moment came after 10 years of preparation and incubation. A wonderfully-creative writer I’ve had the pleasure of working with calls her eureka moment ‘the cessation of stupidity’. Clearly, the lead-up to the creative breakthrough isn’t like lolling around the apple orchard.

- Creative genius takes a certain level of intelligence, beyond which, greater intelligence doesn’t lead to greater creativity. That generally-accepted required intelligence level is an IQ score of 120.

- Creative people tend to be polymaths, people with broad interests in many fields.

- Creative people tend to work much harder than the average person.

- Creative people (and/or their family members) are much more likely than the general population to suffer from depression and bipolar disorder. Artists and scientists alike. Not so much schizophrenia and other mental illnesses often associated with high creativity. While I have my own theories on this, further interpretation is best left to the experts.

Allow me to translate what I think each of the above points means for the marketing world:

- Creative people aren’t necessarily smarter than you, but their brains are wired differently. It’s not like there’s anything wrong with that. And if you think IQ really measures intelligence, you should do some more reading and thinking on the topic, starting with: Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman, 1995.

- Outside of their work, creative people are very diverse, interesting and fun to be with. They can share more than their creativity and they may know more about how the rest of the world works than you do.

- Remember what needs to take place before that eureka moment happens in the shower, shooting hoops or otherwise goofing off. The creative process really does take time unless all the necessary up-front work has already been done—which is rare.

- Creativity is messy. Messy for you but even messier for the creative person. This is not a new concept. 2.3 millennia ago, Aristotle said, “Those who have been eminent in philosophy, politics, poetry, and the arts have all had tendencies toward melancholia.” One of Andreasen’s creative subjects put their personal struggle this way:

“When you have talent and see things in a particular way, you are amazed that other people can’t see it.” Persisting in the face of doubt or rejection, for artists or for scientists, can be a lonely path—one that may also partially explain why some of these people experience mental illness.

Things get tougher at the genius end of the creative spectrum. This is Andreasen’s closing:

In A Beautiful Mind, her biography of the mathematician John Nash, Sylvia Nasar describes a visit Nash received from a fellow mathematician while institutionalized at McLean Hospital in Belmont, MA.

“How could you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical truth,” the colleague asked, “believe that extraterrestrials are sending you messages? How could you believe that you are being recruited by aliens from outer space to save the world?” To which Nash replied: “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously.”

Some people see things others cannot, and they are right, and we call them creative geniuses. Some people see things others cannot, and they are wrong, and we call them mentally ill.

And some people, like John Nash, are both.

- Nancy C Andreasen, ‘Secrets of the Creative Brain‘, The Atlantic, July/August, 2014.

- Main photo credit: ©2001, Universal Pictures (North America).