Throughout human history, winemaking has been a craft industry, ruled by artisans and run by families. In modern times, we believe that categorisation applies even to the big producers in traditional Old World winemaking countries [1]. They got big one of two ways:

- Without marketing but with patience while sticking to their craft (meaning many decades of waiting), or;

- With marketing that never forgets the critical importance of winemaking craft (costing more up front but taking much less time).

New World wineries have often done craft marketing differently.

The Back Story

The Casella family are 5th generation winemakers, originally from Sicily and based in New South Wales, Australia, since 1957. Filippo Casella planted a vineyard in 1965 and in 1969, built a small winery and formed Casella Family Brands (Casella). By Australian standards, the Casellas were beginners and couldn’t compete directly with the premium quality of family wineries that had been perfecting their craft (in many cases) for more than a century. They started as bulk wine producers. In the 1990s, Casella looked to the US market for growth beyond bulk. A serendipitous meeting in 1998 with US wine wholesaler Deutsch Family Wines & Spirits (DFWS) resulted in a 50/50 joint venture. DFWS and Casella launched Carramar Merlot, with a traditional wine label, at just below (then) mid-market prices. It was a failure.

Learning from Failure

Rather than going their separate ways, the two partners decided to try again with some real marketing. This was initially led by DFWS, who had been very successful selling premium Old World wines in America—their biggest brand being France’s Georges Duboeuf Beaujolais.

Family patriarch Bill Deutsch could see that the traditional US wine market in the 1990s had too many competitors chasing too few consumers. Only 10% of Americans were frequent wine consumers and the average retail price point per 750 ml bottle was around $15. To consumers, wine was complex and confusing in the media, on the label and on the crowded store shelf. No new wine drinkers were coming from beer and spirits. Deutsch believed that could happen if a decent bottle of wine could be made at a $6 price point—and that if anyone could do it, it would be a scrappy Australian winery like Casella [2]. At that time, Australian wines had a tiny foothold in America and were competing directly with traditional Old World and California brands.

Marketing from the Ground Up

Casella’s Export Manager, John Soutter, was the senior person responsible for the creation of the [yellow tail] brand, awkward square brackets and all. The guiding principle that [yellow tail] should be the opposite of a traditional wine brand. Enter the aboriginal art-inspired wallaby logo and the minimal label copy that was devoid of wine pretention. The brand launched with one white and one red SKU—a Chardonnay and a Shiraz, easily identified as colour-coded siblings. These varietals were clever choices because they were both new wine tastes to all-but-the-most sophisticated American palettes at that time:

- [yellow tail] Chardonnay was unoaked, so different in flavour profile and cheaper to make than American chardonnays

- [yellow tail] Shiraz is made from the Syrah grape in a style of winemaking unique to Australia

The liquid was described in a wonderfully-backhanded compliment by a Californian wine consultant as, “the perfect wine for a public grown up on soft drinks.” [2] So fruity and simple (or fruit-forward and round, as the cork dorks like to say).

Brand Communications

Brand Communications

For its first few years, [yellow tail] was above and beyond advertising. Word-of-mouth was everything, and at launch, social media had not yet been invented. As soon as the brand owner decided their target market had enough word-of-mouth, on-brand advertising started. Just like Starbucks, Lululemon and soon, Tesla. [yellow tail] now advertises in all major social and traditional media, including Super Bowl TV ads.

Brand Success

From its launch in the US and Canada in 2001, [yellow tail] took North America by storm. It became the biggest import brand by volume in the US by 2003 at 3.0M cases, and the biggest in revenue by 2005 at $621M (USD) [3]. In 2003, Casella launched a ‘reserve line’ of [yellow tail] at a $2 to $3 (USD) per bottle premium. That brand extension was phased out in favour of more varietals & blends, sparkling wine, sangria and low-alcohol extensions. All this brand extension has been done within strict brand guidelines.

Casella now sells 13.5M cases a year worldwide ($360M), about half of that in the USA, followed by the UK, Australia and Canada, plus more than 50 other countries [4]. It’s not clear if global brand sales have plateaued yet. According to UK-based Wine Intelligence, [yellow tail] is the Most Powerful and Most Loved Wine Brand [in the world!] four years running (2018-2021).

The House that [yellow tail] Built

[yellow tail] has turned Casella, though still family-owned, into a major global wine producer and distributor. Casella has gone on to create mid-range Magic Box brand, high-end (and highly-awarded) Casella Family Wines Limited Release and organic CSR-conscious Atmata brand. Since 2014, [yellow tail] has also allowed Casella to acquire a portfolio of premium international award-winning Australian brands.

Today, Casella presents itself as the creator and owner of many of Australia’s most prestigious brands, but it acknowledges that [yellow tail] is still their biggest, and the one that made their success possible.

The Back Story

In the early 1900s, Andras Peller was born to an ethnic German family near Budapest, Hungary. He became an engineer and mechanic, started a young family and emigrated to Canada in 1927. He worked as a mechanic in Kitchener and then Toronto, where he also worked in a brewery. In 1945, Andras started Peller Brewery in Hamilton and by the 1950s, it was doing well enough to be acquired. Then came a series of unrelated business ventures in Hamilton: a car dealership, a grocery store and a newspaper. None of these worked out particularly well, so Andras moved to British Columbia, planted a vineyard in the Okanagan Valley and in 1961, built the first winery for quasi-eponymously-named Andrés Wines Ltd (Andrés) in Port Moody.

Marketing by Trend-Spotting

Leading up to the 1960s, the most popular Canadian wines were ports and sherries. That’s because the cold-climate grapes grown at that time were of lower quality and needed extra sweetness to make their wine more palatable. Extra alcohol content also allowed Canadian fortified wines to more closely match their Old World big brothers in flavour profile—which was not achievable in table wines. How sparkling wines became popular in the 1960s is unclear, but the slight tartness of carbonation reduces the perception of sweetness—and creates the light mouthfeel of soft drinks.

The first real global wine brands were French champagnes Dom Pérignon and Moët et Chandon and where gaining ‘aspirational popularity’ through North American culture. But they were out of reach for most wine consumers—and definitely for special occasions.

Inexpensive sparkling wines from the US (Cold Duck) and Portugal (Mateus) were also gaining popularity at this time. In the mid-1960s, a number of Canadian wineries, including Andrés, launched their own versions of the US-inspired Cold Duck. Some were at 7% alcohol by volume (ABV), half the content of standard wines, allowing for a lower price point [5].

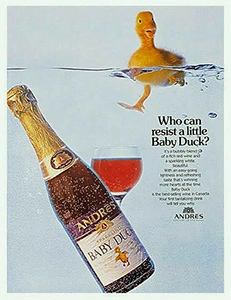

Andras, now with his son Joe as Andrés’ President, looked at all of these trends and launched Baby Duck in 1971. Andrés tried to register Baby Duck as ‘Canadian champagne’ and failed [6]. But the bottle shape, caged plastic cork and foil dressing created the impression it was ‘Baby champagne’ [7]. At 7% ABV and using inexpensive grapes, it was the cheapest thing on the retail shelf that looked like champagne.

Brand Communications

Brand Communications

Andrés invested heavily in traditional print and TV advertising. The ducklings created the impression the brand was cute, innocent fun. The print ads won Clio awards. The TV ads did not, but required serious duckling wrangling.

Brand Success

Baby Duck took Canada by storm, going from zero in 1971 to more than 8M 750 ml bottles (667k cases [8]) in 1973. Applying the 10x rule, Baby Duck was as successful by volume in Canada as [yellow tail] was in the US. By 1975, it represented a record 25% of all wine sales in the province of Ontario. It remains the most financially successful wine brand launch in Canadian history. It remains in the market, selling an estimated 100,000 750ml bottles (8,335 cases) in 2022 [9]. It also remains undrinkable by today’s standards, even allowing for the nostalgia factor [10].

The House that Baby Duck Built

Andrés went public in 1970 as plans for the launch of Baby Duck were developing. The IPO helped fund the Baby Duck launch, the success of which made Andrés an excellent investment over the first 10 years. Andrés launched more me-too value wine brands during the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, they got serious about moving up the wine quality spectrum. They did this through acquisition of mid-market wineries like Hillebrand, and in 2001, opened Peller Estates Winery at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

In 2006, Andrés rebranded as Andrew Peller Ltd. This was followed by acquisitions of more award-winning premium wineries, and in 2017, super-premium wineries. Since 1995, Andrew Peller has made 18 acquisitions for more than $210M. It now accounts for 37% of Canadian domestic wine sales by volume [11].

Today, mention of Baby Duck is nowhere to be found on the Andrew Peller website. The Andrew Peller name appears on the current Baby Duck label, as required by law, but at the tiny minimum legal size.

Craft Marketing Lessons

What do our two tales teach us about craft marketing? There are many similarities in [yellow tail]/Casella Family Wines and Baby Duck/Andrew Peller stories, big financial success in the same craft industry being the most obvious. The important lessons might be in the differences.

Lesson 1: The Artisan vs the Business Person

The artist, or artisan, strives to make people see, hear, taste or think about the world differently.

Filippo Casella was a multi-generational Old World winemaker. His children who run Casella are too. Andras Peller was a serial entrepreneur who loved wine. His son Joseph left a very successful medical practice to run Andrés. Joseph’s son John, who became president of Andrew Peller in 1992, was a lawyer who also worked at Nabisco Brands in corporate planning and development.

The under-rated 1996 movie Big Night is about staying true to your art while pursuing The American Dream. In a key scene, Pascal, the business-focused restauranteur, tells the craft-oriented restauranteur:

Andrés gave Canadians what they wanted with the launch of Baby Duck. It made money but it didn’t move the Canadian wine industry forward domestically or internationally. Nor did Andrés move very quickly at delivering on their often-stated mission of giving Canadians better quality wine (the what you want part of Pascal’s advice). The Casella family achieved all of the above, proving that in craft industries, you can be both artisan and business person. Also, when your craft brand is pushing consumers outside their comfort zone, as [yellow tail] was, the brand needs to be positioned well. This leads to long-term success.

Lesson 2: Know When to Kill a Brand [12]

Andrew Peller should have killed Baby Duck as it started to decline in the early 1980s. Definitely by the mid-1990s when it’s premiumization strategy was playing out. The company has not needed Baby Duck’s revenue contribution for decades and it’s not like they’re proud of the brand. Never mind what consumers think for a moment, what are the employees who are bottling Baby Duck thinking about their company’s mission statement?

- This is our opinion, perhaps no one else’s. We’re referring specifically to France, Italy and Spain.

- Frank J Prial, “The Wallaby That Roared Across the Wine Industry”, nytimes.com, Apr 23, 2006.

- “Australian Wine Brand Secures No. 1 Ranking in U.S. Sales”, winespectator.com, Oct 10, 2006.

- Mike DeSimone & Jeff Jenssen, “Yellow Tail Celebrates 20 Years of Growth and Innovation”, forbes.com, Dec 23, 2021.

- Robert Bell, winesofcanada.com.

- Caroline Charest, “Manufacturing Authenticity – A Case Study of the Niagara Wine Cluster”, Brock University Master of Arts thesis, Oct, 2009.

- Andrés Baby Champagne is sold in the US. In Canada, except for Ontario, it’s sold as Andrés Baby Sparkling.

- A standard case of wine or spirits in North America is 9.0 litres.

- Estimate by Coyote based on LCBO retail inventory at Dec31-23, average LCBO inventory turn and current provincial proportions of total Canadian wine sales.

- Carolyn Evans Hammond, “Which LCBO standby stands up better than the rest?”, thestar.com, Jan 17, 2020. Carolyn is a wine expert, definitely not a cork dork. I tested Baby Duck myself and agree with the verdict. It did, however, make my kitchen sink drain run a bit faster.

- Andrew Peller Limited Investor Fact Sheet, Q1, 2023.

- By unfortunate coincidence, Mark Ritson covered this topic last week.