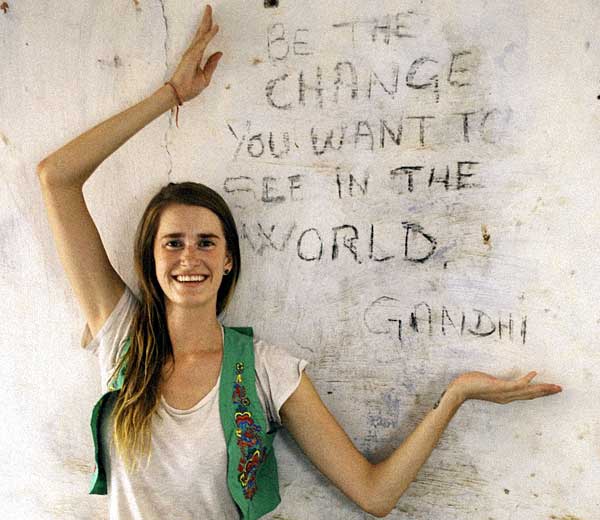

While you can argue that doing good has nothing to do with generations or cohorts, it is clear that

First up – do Millennials give any more than previous cohorts? The answer is yes, but it’s a different kind of giving. Forbes recently did a good summary of the current research on this: [2]

- You often hear the statement, “Millennials want to give to causes and people, not to organisations or corporations”. Thank-you, Captain Obvious, but that doesn’t make Millennials unique. I think the wordsmithing on this often-used statement is off. Millennial do-gooding is grassroots and in many small, crowd-sourced increments. Grassroots doesn’t necessarily mean local, it means personally connecting with the people who need the help.

- The currency of do-gooding is more time and personal effort than it is dollars. Volunteering was a formalised part of the Millennial education.

- Millennials are more interested in actively fund-raising than they are in personally donating money. Again, the former has been a big part of the Millennial education.

So Millennials would rather crowdfund, build and volunteer at an out-patient cancer therapy recovery centre than make a regular monetary donation to a big institutionalised charity like the Canadian Cancer Society. Obviously, Big Charity needs to change because we still need to beat things like cancer and most Millennials can’t be directly involved in fixing it.

Millennials’ active fund-raising mentality is obviously behind the demand that their brands and the organisations that employ them be equally in social responsibility.

Second up – what brand do-gooding works the best in the Millennial context? I’d have to say, “It depends what the objectives are.” Consider these three diverse initiatives:

Ikea’s “Better Shelter” homes for refugee camps

Over the last few years, Ikea has been working with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to improve the refugee camp shelters, which typically have been tents without utilities/amenities and last for a few months. Ikea designed the Better Shelter the same way they design their furniture. They are compact, insulated and lockable structures that last three years, come with solar lighting & phone charging, ship in super-efficient flat packs and go together with little more than an allen key. They are palaces by refugee camp standards and are being built and sent to places like Iraq and Ethiopia by the tens-of-thousands. Ikea funded the design & development so that the structures can be affordably produced by others and purchased by organisations like the UNHCR.- Volvo’s LifePaint

Cycling’s is increasingly popular in London (UK), but the city has 19,000 car-cyclist accidents a year and a rising number of them are fatal to the cyclist. LifePaint is a spray-on, washable product containing reflective particles which are invisible by day but light up at night in the glare of headlights. The idea came from Volvo’s UK agency, Grey London, and was developed by a technology partner. It manages to highlight the pedestrian, cyclist and the pedestrian & cyclist detection system in all of Volvo’s vehicles. The Volvo-branded LifePaint product is in regional roll-out now. - Pedigree’s “First Days Out”

For 10 years now, The Pedigree Foundation has been active in saving abused, abandoned and otherwise homeless dogs. They have also been involved in dog training programs in the US prison system. With their agency Almap BBDO, Pedigree recently took those efforts an important step further. They helped just-released ex-convicts adopt a companion dog to aid in the very difficult process of re-adjusting to society. Two real stories and people from that initiative became the subjects of branded video creative.If the do-good objective is to help as many people in true dire need as possible, Ikea wins. But it’s not grassroots and it’s hard for North Americans to visualise how people’s lives are changed. Part of the reason is that Ikea has chosen to not promote their initiative in their marketing, despite the fact that the company invested much more money in their do-good effort than in the other two brand examples.If the do-good objective is to directly link the good deed with the brand, Volvo wins. The problem is a real grassroots issue in major urban centres, helped by a brand that is directly linked to the problem. It’s also perfectly in line with the brand’s overall safety positioning.

If the do-good objective is to link the brand to very strong positive emotion, Pedigree wins. It’s very grassroots and local. I’m not sure how many people understand how big the returning-to-society issue is in the USA, which has the highest per capita prison population in the world. Helping ex-convicts helps everyone.

Which do-good efforts appeal most to Millennials? If they are pet lovers, and most of them are, it has to be Pedigree. Beyond the dog content, the creative has a (very well done) reality TV/story-of-redemption feel to it and it is easily shareable. The benefits of the Volvo and Pedigree deeds are in small increments compared to Ikea’s, but remember, Millennials want all their brands and employers to do this sort of thing.

Though it wasn’t my intention, both the Volvo and Pedigree do-good deeds involved marketing partners. There are creative ways to meet everyone’s do-good and business objectives.

Notes and references:

- Feature image credit: Megan Doepker of UNA Fashion, poster girl for Millennial do-gooding

- Ryan Scott, Millennials Rule at Giving Back, Forbes, Jan 18, 2015.

Great to see that Volvo’s Life Paint just won the Promo & Activation Grand Prix at Cannes. I say that because it’s strategically great for the brand as opposed to only being creatively brilliant for the brand.