The October 16th Globe & Mail Report on Business (online edition) carried an article titled “Beer giants’ merger comes as the industry tries to get its buzz back”. In it, and in the print version of the same story in the weekend edition following, Globe reporter Susan Krashinsky provides a good summary of Canadian beer industry dynamics. Her thesis is that the proposed mega-merger between AB InBev and SABMiller is the only option the Big Brewers have for beer volume growth.

More interesting to me was the discussion of the craft beer segment—a topic that always comes up because it’s the only growth segment in the industry. What’s the Big Brewer strategy against craft beer brands? Buy them and continue to market them as craft brands. And according to every Canadian journalist’s inevitable go-to-guy for beer branding, David Kincaid, [1] this is part of an on-going cycle.

Which begs the obvious question, ‘Does craft need to be authentic?’

First off, there isn’t an agreed-upon or legal definition of what craft is. Craft brewing associations tend to look at three things to determine if you qualify for membership:

- Small annual production volume. In Canada, the limit is usually 400,000 hectolitres (huge at 1.7% of total national beer volume). In the US, it’s the equivalent of just over 7,000,000 hectolitres (4% of total US beer volume, which would be 30% of total Canadian beer volume).

- Independent ownership. Not absolute, though—75% minimum in the US and ‘significant’ in Canada (whatever that means).

- Traditional ingredients. Also not well-defined, ‘innovative’ ingredients are okay too. Let’s hope Monsanto doesn’t engineer water, brewers’ barley, hops or yeast.

At such high numbers, current volume limits aren’t particularly useful in defining craft. Something in the 20,000 hL range would make more sense. And the ownership percentage seems a bit contrived—you either brew your beer independently or not, and that freedom doesn’t always relate directly to ownership.

From the consumer’s perspective, the craft concept should be about the quality of the beer, which is most directly determined by natural ingredients and a small-batch traditional brewing process. I would also add the associated nuance that to be authentic craft, the beer needs to be brewed in a single dedicated facility. These proposed definition parameters tend to create practical limits on production volume and geographic distribution.

If what I’m suggesting became the de facto definition of craft, there would be some interesting re-categorisations:

- Creemore Springs Brewery (owned by Molson-Coors) would return to authentic craft status—it’s still made with all natural ingredients and a traditional small-batch brewing process in the same expanded (but dedicated) brewery.

- Granville Island Brewing (same basic starting point as Creemore Springs and also owned by Molson Coors) would remain as NOT authentic craft—now most of it is brewed in a Molson facility in Kitsilano, BC, ‘monitored’ by a Granville Island ‘representative’.

- Steam Whistle Brewing’s authentic craft status would remain unchanged.

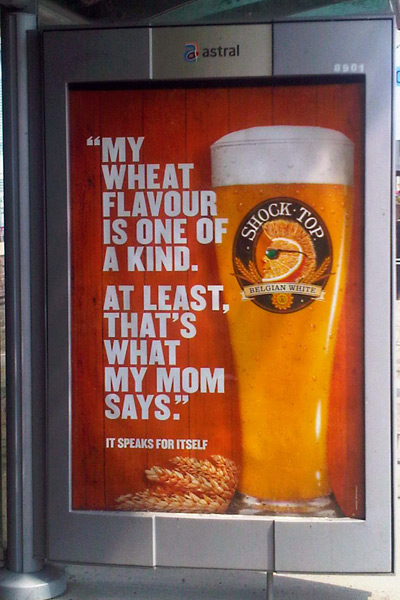

Does a craft brand owned by a Big Brewer have a marketing advantage over independently-owned (meaning smaller) craft brands? Consider Shock-Top, brewed in St Louis, KY, and owned by AB InBev, the world’s biggest brewer by volume, about to become even bigger.

Does a craft brand owned by a Big Brewer have a marketing advantage over independently-owned (meaning smaller) craft brands? Consider Shock-Top, brewed in St Louis, KY, and owned by AB InBev, the world’s biggest brewer by volume, about to become even bigger.

Shock Top ran this transit shelter ad (at right) in Toronto, giving the brand a cool local craft feel. I’d go as far to this ad is Millennial-clever, seemingly everyone’s goal in the category. But these ads ran nationally in Canada and the ‘‘It speaks for itself” slogan was paid-off literally with talking outdoor boards, talking on-premise beer taps and talking beer bottles flown in to unsuspecting patio patrons by drones—making for particularly shareable moments. Not something your average craft brewer can even dream of affording.

I’d argue Shock Top has done good brand advertising that has nothing to do with authenticity. One of the true things you hear about Millennials is their media savviness. They can sniff out non-authentic messaging in a heartbeat, if they care to. Authenticity is reported to be a brand mandatory for Millennials and has also been a prerequisite for other cohorts in other product categories over the history of modern marketing.

Unlike the Big Brewers, I think craft beer drinkers still demand authenticity and to a large extent, this levels the playing field, at least in marketing communications.

- David Kincaid, Managing Partner & Founder, Level5 Strategy Group.

- Main image: Wooden hand-carved drinking vessel, 17th century, attributed to the Holy Dormition Pskovo-Pechersky Monastery, Russia.

Shortly after this was posted (and by shear coincidence) Molson Coors did a rebranding of Granville Island Brewery that included hiring a new brewmaster with BC craft credibility for the Granville Island facility. Under Kevin Emms, new specialty and seasonal products unique to the original brewery were launched. This ‘innovation brewery’ concept is common for major North America breweries to manage the authenticity of their acquired craft brands.